Context RTA Exhibition at Object Space 2019

Beyond the Neighbourhood

There a number of places in the world where a single architect has produced a whole neighborhood. Over the course of nearly forty years, Pritzker Prize-winner Fumihiko Maki, serving a single family as client, worked his way down a leafy Tokyo boulevard, designing offices, apartments, shops, art galleries, an embassy, and eventually a building to house his own studio. The antithesis of Maki’s genteel refinement, Eric Owen Moss reworked the Los Angeles neighborhood of Culver City, converting old warehouses into aesthetically boisterousoffices for key players in the movie industry, his mode evolving across thirty years from PoMopopism to digitally-derived pleats and swirls. Closer to home, we could look to Cecil Wood’s work at Christ College in Christchurch, or Architectus’ string of projects on the campuses of adjacent high schools in Mount Eden.

These collections of buildings are remarkable in presenting on one sweep the evolution of an architect’s thinking over time, and in demonstrating how powerfully a few well-designedbuildings can set the tone of a neighborhood. RTA Studio are cooking up their own neighborhood in Ponsonby. In one city block they have produced the sugar-dusted confection of the Mackelvie Street Shopping Precinct (2012), it’s villainous black counterpart the Pollen Street Office (2016), and then, like the love-child of the two, Objectspace (2017), its pure white geometric façade hovering against a gritty black background. The block also contains a number of smaller projects including offices and bars.

This city block is the fulfillment of the early promise of RTA Studio, where faced with tightly constrained sites, limited budgets, or the need to reuse existing structures, they created buildings of remarkable strength and clarity. From those early days, RTA Studio sawthemselves as contextualists. For most, the contextual approach involves close reading and thoughtful intervention – given a site, the architect takes a long look to the left and the right, and massages what they find into their design. The result is careful and courteous, the design demonstrating the diligent study of materials, alignments, and references. But where others might have been deferential, RTA Studio are aggressively contemporary. This approach is exemplified by RTA Studio’s 440 Richmond (2004) project, where a façade inserted into a row of heritage shops translated the proportions and rhythms from adjacent buildings into its composition of sculpted concrete. At 582 K’Rd (2008), the facades of badly butchered old buildings were masked by concrete panels and veils of punched metal, with the few surviving heritage remnants left to poke out around the edges, flatteringly suggesting the old buildings were in better shape than they were.

But walk a few minutes in any direction from Objectspace and you’ll find recent RTA Studio buildings that don't fit this mode – a prismatic suburban house, the roof of a school folded into a lightning bolt, or a villa decomposed into shards. In recent years, RTA Studio have moved beyond both the old neighborhoods and their early patterns of work. The firm’s work has dramatically expanded, not just in the expected sense of making larger buildings, but also in the range of building types they undertake and in their geographic extent. Where previously almost all of the firm’s key projects could be spotted from the top of Mount Eden, they now span the country. Prolific to the point of relentlessness, and often collaborating with other architects or advisors to extend the fields in which they can work, their recent roster includes huge apartment buildings, whole school campuses, industrial buildings, and luxurious mountain retreats. In the dense city blocks of the urban fringe, context is unavoidable, with the surrounding buildings literally pressing up on each side. In their new range of settings, RTA Studio escaped this pressure but sought to retain contextualism at the core of their approach. They needed, therefore, an expanded range of contextual design tools.

In the inner city suburbs, the spatial porosity allowed for freer play with formal references. The House for Five (2010) took the silhouette and delicate fretwork of its neighboring villas and bungalows and abstracted them into a decorated prism. The E-Type House, produced four years later and just a few hundred yards away, took greater liberties, quartering the neighborhood’s typical pyramidal roof form and reassembling it as a miniature hillside village, the repetitive form standing equal parts familiar and foreign among the rows of villas.

In rural areas, RTA’s early work seemed to follow a couple of strategies. The first is almost conventional in Aotearoa New Zealand - drawing on our building traditions of the whare and the woolshed, RTA made sheds. For the early project for Mahurangi Winery (2002), the agricultural references were dialed up, with skylights made to look like rooftop water tanks. If anything, shed making has proliferated in recent work; the house at Bob’s Cove in Glenorchy(2018) is a whole village of sheds.

But where other early projects employed general landscape allusions – to local geomorphology, or to mist on the mountains – recent projects show the use of a new and very specific idea: ley lines. These lines stem from the belief that invisible lines in the landscape linking points of spiritual significance, and the idea has been employed in projects like the Tūrama house (2017) in Rotorua and the new campus for Tarawera High School(2016) on the fringes of Kawerau. In both cases, a generous sense of shelter was created with a large folding roof, and the form and space sculpted by lines that reach out points of specific interest. At Tarawera, these lines lead to points of significance to local iwi – the river, the mountain, the coast. At Tūrama, a house built for an extended Maori family that have occupied the site for 16 generations, the lines link to places of significance to family history including burial places and distant points of origin. Ley lines might sound like another reference to physical context, but the shrewdness here is that RTA Studio have found a point of contact between physical and cultural contexts. In finding a way to link a building to the meaning of its context rather that its form, they have found a way of encoding architecture that maps precisely over the Māori sense of identity and position being defined by elements in the landscape. This may prove to be a major contribution to the development of architecturein Aotearoa New Zealand.

One of the criticisms that is made of architects, though not unfairly, is that so much of theirbest work is private, inaccessible to those who can’t afford their services. While RTA Studio’s portfolio includes luxurious houses, it also includes a surprisingly wide range of other work – from modest homes to schools, universities, and factories – that make architecture available to a wide range of people. The most obvious contexts are physical and formal, but this is only one kind of context. Much of the evolution of RTA’s work has been driven by a desire to make work that is embedded in its social context, that is socially engaged. This encouraged them, in particular, to take on school design, and even to gift their services to the community – Objectspace, for example, was a pro bono project.

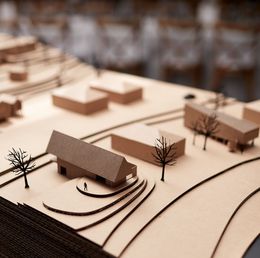

Coinciding with the 20th anniversary of RTA Studio’s formation, this exhibition shows therapidly expanding range of their work. That range spans from tiny houses to an industrial building so large only a corner of it could fit on the model, and from low-budget renovations to a swathe of the Auckland waterfront. But despite this variety, what shines through is a sense of clarity, even when the contexts being drawn in extend beyond the horizon, and that this is architecture that seeks to make a contribution – to the neighborhood, to the community, and to the development of our architectural culture.